Frida Kahlo’s art is more than visual—it’s emotional narrative, cultural identity, and personal symbolism rolled into color and canvas. While many artists paint what they see, Frida painted what she felt. Her most iconic works reveal inner turmoil, political beliefs, and complex views on gender, love, and heritage.

This article explores the recurring symbols and metaphors that appear throughout Frida Kahlo’s most important paintings and how they helped shape her into a global artistic and feminist icon.

The Power of Self-Portraiture

Frida as Her Own Subject

Frida Kahlo painted more than 50 self-portraits. She often said, “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.” Her face became her canvas, but it was rarely just a literal likeness—it was a symbol of identity, strength, and suffering.

Through her gaze, costume, and background, Frida created an ongoing visual diary of her emotional and physical state. These portraits weren’t just autobiographical—they were layered symbols of womanhood, pain, and self-awareness.

Common Symbols in Frida Kahlo’s Iconic Works

1. Thorn Necklaces and Bleeding Hearts

In Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), Frida wears a thorn necklace digging into her neck, drawing blood. The thorns represent suffering and martyrdom, reminiscent of Christ’s crown of thorns. The hummingbird—normally a symbol of hope—is black and lifeless, perhaps indicating lost love or emotional exhaustion.

Behind her, a monkey tugs on the thorns while a black cat looms, adding tension and a sense of danger. Kahlo’s expression remains calm, reinforcing the idea of endurance through agony.

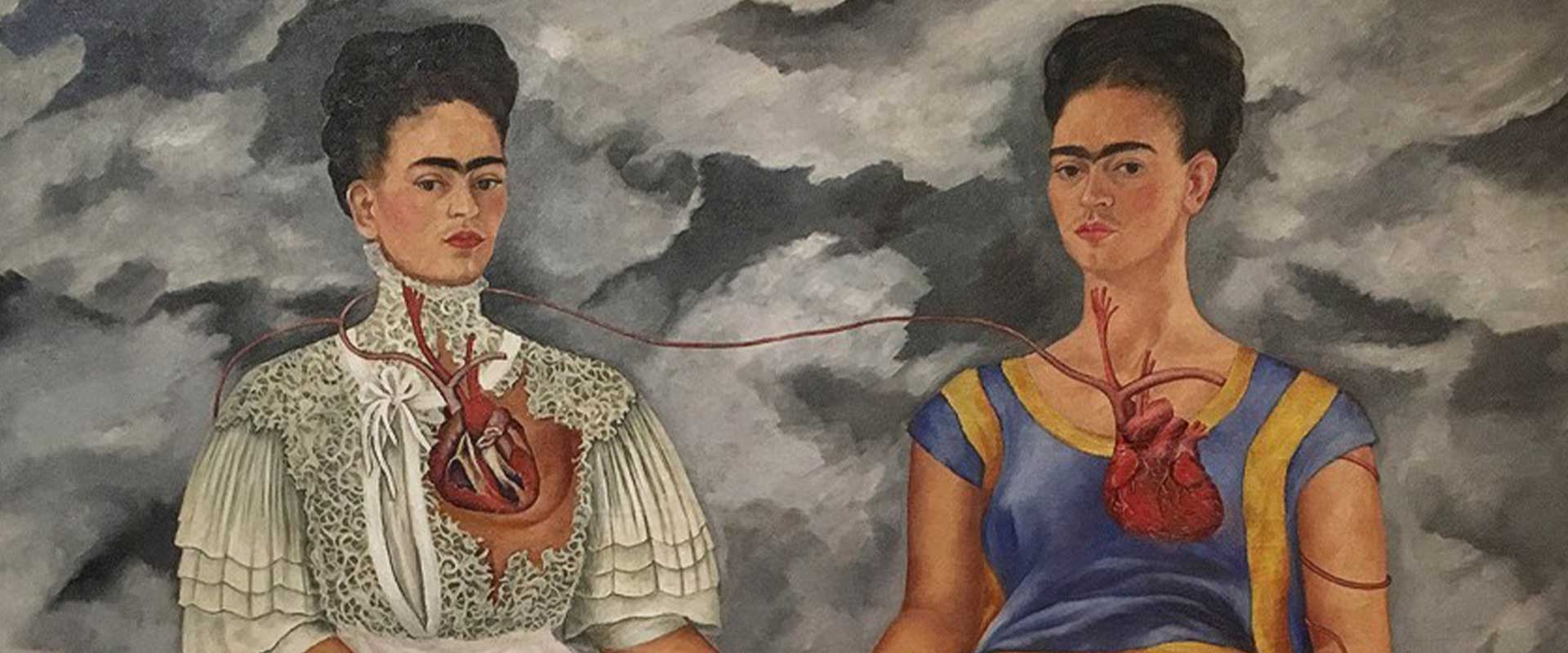

2. Duality and Inner Conflict

The Two Fridas (1939) is a massive double portrait painted after her divorce from Diego Rivera. It shows two versions of Frida sitting side by side: one in a European-style white dress with an open heart, the other in traditional Mexican attire with a healthy, intact heart.

The exposed hearts are connected by a vein, yet one bleeds onto her lap. This contrast reflects emotional duality—Frida as loved and unloved, healed and broken, colonized and native. It’s one of her most powerful explorations of split identity.

3. Broken Bodies and Medical Trauma

Frida Kahlo lived with intense pain for most of her life due to childhood polio and a devastating bus accident in her teens. Her painting The Broken Column (1944) lays her suffering bare.

In it, she depicts herself with her torso cracked open, revealing a shattered ionic column as her spine. Her face is stoic, but her body is pierced with nails. The barren background mirrors her desolation. The work is a raw symbol of chronic pain, emotional isolation, and physical vulnerability.

4. Nature, Animals, and Mexican Identity

Frida’s inclusion of flora and fauna often goes beyond decorative detail. In many of her paintings, she is surrounded by monkeys, dogs, parrots, and plants. These elements reflect her connection to Mexican folklore, Aztec mythology, and earthly femininity.

For example, in Self-Portrait with Monkey (1938), the monkey represents playful curiosity but also emotional attachment—possibly alluding to Diego Rivera, who gifted her monkeys. The background is lush and fertile, contrasting the emotional restraint on her face.

5. Indigenous Culture and Feminism

Kahlo often wore Tehuana dresses, associated with matriarchal societies in Oaxaca, Mexico. This choice wasn’t just fashion—it was a political and feminist symbol.

In Self-Portrait Dedicated to Dr. Eloesser (1940), she wears such a dress, proudly declaring her heritage while subtly referencing her loyalty to her doctor who supported her through surgeries. Her attire often acted as a shield, empowering her to reclaim control over her body and image.

6. Maternity, Loss, and Identity

Henry Ford Hospital (1932) is one of Kahlo’s most emotionally charged paintings. It depicts her lying on a hospital bed, bleeding and weeping, following a miscarriage. Six elements float around her: a fetus, a snail, a mechanical structure, a pelvic bone, a female reproductive system, and a flower.

Each object connects to her via red veins, representing both life and death. This painting reveals Frida’s grief, infertility, and helplessness, but also her commitment to expressing the rawest parts of womanhood.

Political Symbolism in Frida Kahlo’s Paintings

Frida was a lifelong communist and often infused her political ideology into her paintings. Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (1954) shows her throwing away her crutches as she embraces a large figure of Karl Marx.

Her portrayal of politics, class struggle, and Mexican sovereignty made her art not just personal but revolutionary. Even her body—disabled, brown, and female—became a political statement against the ideals of Western beauty and perfection.

The Personal Is Universal

While rooted in autobiography, Frida Kahlo’s paintings are revered because they tap into universal experiences: pain, love, betrayal, loneliness, and hope. Her genius lies in how she transforms intimate anguish into visual poetry.

Even without understanding her full life story, viewers feel connected to the emotional truth that radiates from her work. Her symbols are not cryptic—they’re powerful, clear, and deeply human.

Frida Kahlo’s Symbolism in Modern Culture

Frida’s symbolic imagery continues to influence artists, designers, and activists. Her flowers, monkeys, broken bodies, and dresses appear in pop art, street murals, and fashion campaigns.

But it’s not just aesthetics that captivate people—it’s the storytelling behind each element. Every detail in a Frida Kahlo painting carries weight, making her work both beautiful and brutally honest.

Add Frida Kahlo’s Story to Your Space

Inspired by Frida’s iconic use of symbols and her deeply personal art? Explore our Frida Kahlo wall art prints to bring her powerful imagery into your home.

Looking for more legendary art? Visit our artists collection for timeless canvas prints that reflect boldness, depth, and culture.

Conclusion

Frida Kahlo didn’t just paint what she saw—she painted what she lived. Her use of symbolism created a new language of personal and political expression that still resonates today.

From bleeding hearts to fractured spines, Tehuana dresses to black cats, every element in her paintings is deliberate and deeply meaningful. By exploring the symbolism in Frida Kahlo’s most iconic paintings, we don’t just learn about her art—we understand her life.

FAQ

What symbols appear most often in Frida Kahlo’s art?

Recurring symbols include thorn necklaces, monkeys, hearts, indigenous clothing, blood, flowers, and animals—each representing aspects of pain, love, and identity.

Why did Frida Kahlo paint so many self-portraits?

Frida often said she painted herself because she was frequently alone and knew herself best. Her self-portraits served as a personal and emotional outlet.

How did Frida Kahlo use symbolism to represent pain?

She used imagery like broken columns, nails, blood, and exposed hearts to portray physical and emotional pain in a visceral way.

Are Frida Kahlo’s paintings political?

Yes. Her art includes elements of Mexican identity, feminism, Marxism, and anti-colonial themes, often symbolized through attire, iconography, and subject matter.

Which painting is considered Frida Kahlo’s most symbolic?

The Two Fridas is often considered one of her most symbolic works, exploring duality, emotional wounds, and identity through mirrored self-images.