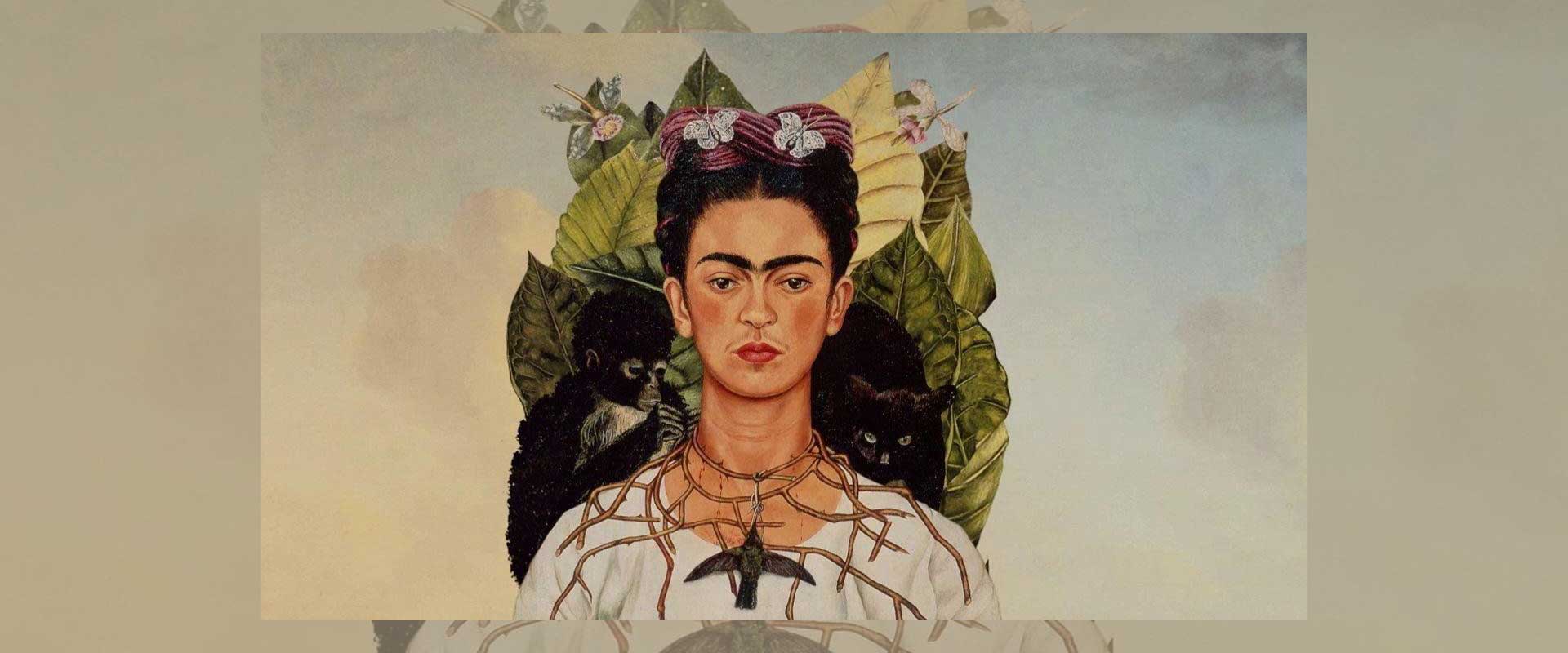

Frida Kahlo’s paintings are among the most personal and symbolically rich works in modern art. Her self-portraits in particular are filled with objects, animals, plants, colors, and background elements that carry layered meanings. For Kahlo, symbolism was not ornamental—it was a deliberate visual language through which she expressed her physical suffering, emotional struggles, political beliefs, and cultural pride.

She often combined influences from Mexican folk art, indigenous mythology, Catholic iconography, and her own life experiences to create compositions that could be “read” as much as they could be admired visually. Whether you encounter her work in a museum or browse curated collections like the Frida Kahlo Wall Art Prints, understanding her use of symbols transforms the experience into a much more intimate connection with the artist herself. Her use of symbolic motifs also links closely to themes explored in Frida Kahlo’s Impact on Contemporary Art and Pop Culture.

The Role of Symbolism in Kahlo’s Art

For Kahlo, every visual detail had intention. She layered symbols in her paintings to:

- Represent deeply personal events such as miscarriages, surgeries, and relationship turmoil

- Connect with broader cultural narratives of post-revolutionary Mexico

- Explore identity through clothing, heritage, and physical appearance

- Merge reality with imagined or dreamlike elements to heighten emotional truth

This approach allowed her to create images that could be appreciated both for their immediate beauty and for the personal and political stories they carried.

Common Symbols in Frida Kahlo’s Paintings

| Symbol | Meaning | Example Painting |

|---|---|---|

| Monkey | Playfulness, protection, or mischievous desire | Self-Portrait with Monkey (1938) |

| Thorn Necklace | Suffering, sacrifice, and resilience | Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) |

| Hummingbird | Hope, love, or spiritual freedom | Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) |

| Heart | Emotional pain or passion | The Two Fridas (1939) |

| Roots | Connection to land, heritage, and permanence | Roots (1943) |

Nature as a Symbolic Framework

Nature is one of Kahlo’s most consistent symbolic frameworks. She often surrounded herself with lush foliage, flowers, and fruit, not simply for aesthetic beauty but to reflect growth, vitality, and the cycles of life. Flowers like marigolds, often used in Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebrations, could represent both life and remembrance. Vines and leaves intertwining with her figure suggested the inescapable ties between humanity and the natural world.

In works such as Roots, Kahlo merges her body with the earth, plants literally sprouting from her chest, reinforcing ideas of fertility, sustenance, and connection to cultural origins. These botanical symbols draw from indigenous Mexican beliefs in the life-giving power of the land and its sacred relationship with people.

Animals as Emotional Proxies

Animals in Kahlo’s paintings often stand in for emotional states or symbolic themes. Monkeys, frequently appearing in her self-portraits, were traditionally considered symbols of lust or mischief in Western art, but Kahlo gave them a protective and affectionate role, often draped over her shoulder as companions. Dogs, especially the hairless Xoloitzcuintli breed native to Mexico, appear as symbols of loyalty, ancestry, and the underworld in Aztec mythology.

Birds in her art, such as parrots and hummingbirds, carry varied meanings. Parrots suggest exotic vibrancy and freedom, while hummingbirds—often associated with love and resurrection in Mexican folklore—sometimes appear lifeless in her work, reflecting personal grief. In Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, the bird hangs lifeless, symbolizing lost hope or unfulfilled love.

Religious and Spiritual Iconography

Kahlo’s upbringing in a Catholic household and her fascination with indigenous spirituality gave her a unique visual vocabulary for depicting suffering and resilience. Sacred hearts, thorn crowns, and saint-like poses link her experiences to a universal narrative of endurance and sacrifice. In The Two Fridas, the exposed heart and arteries between the two figures evoke both emotional pain and religious martyrdom.

She often merged Catholic imagery with Aztec symbols, creating a hybrid spiritual language. This duality reflects Mexico’s complex cultural identity and her own belief in the coexistence of multiple traditions.

Symbolism in Color Choices

Kahlo’s color palette was never random. She used color to amplify the emotional resonance of her work:

- Red: Intensity, passion, pain, and vitality

- Blue: Calmness, melancholy, spirituality

- Green: Life, renewal, and hope

- White: Purity but also vulnerability when contrasted with blood imagery

In The Two Fridas, the clean white dress of one figure is stained with blood, making the contrast between innocence and trauma more powerful. The stormy blue-gray background heightens the painting’s emotional weight.

Political and Cultural Symbols

As a supporter of post-revolutionary Mexican nationalism, Kahlo used her art to express political and cultural identity. She incorporated indigenous motifs, pre-Columbian artifacts, and traditional Mexican clothing into her self-portraits. Her Tehuana dresses were not just personal style but a visual assertion of her pride in her heritage, rejecting Westernized fashion in favor of indigenous traditions.

These political statements were subtle but impactful, aligning her with the cultural movements that valued folk traditions as part of Mexico’s modern identity. This cultural pride parallels works seen in the broader Artists category, where heritage often drives artistic style.

How to Read Kahlo’s Symbolism

When approaching Kahlo’s paintings, viewers can decode her symbols by:

- Identifying recurring objects, animals, and plants and researching their cultural meanings in Mexican tradition

- Observing her clothing choices and hairstyles for political and personal significance

- Noting her use of color and how it interacts with the symbolic elements

- Considering the biographical and political context of the painting’s creation

This layered reading enriches the viewing experience, turning each painting into a dialogue between the artist and the audience.

Conclusion

Frida Kahlo’s use of symbolism turns her paintings into intricate narratives that transcend time and place. Her visual language—rooted in personal experience, cultural heritage, and political belief—creates a multi-dimensional form of storytelling. From monkeys that guard her to thorn necklaces that record her suffering, each element invites us to look deeper. Understanding her symbolism not only enhances appreciation for her art but also connects us to the resilience and identity she fought to preserve.