Picasso didn’t just influence modern art—he rewired how we see. Across seven decades, he broke, rebuilt, and reimagined forms so that painting became a field for invention rather than imitation. From the austere blues of his youth to the collision of angles in Cubism and the fierce activism of Guernica, Picasso changed what a picture could be and what it could do. In this complete guide, you’ll discover the stages of his evolution, the techniques behind his most radical breakthroughs, and how his ideas still drive today’s visual culture. If you want to bring his vision home, explore the curated Pablo Picasso wall art collection at Canvas Wall Prints.

Why Picasso Still Matters

Picasso matters because he proved that painting can think. Instead of chasing lifelike resemblance, he pursued multiple viewpoints, fractured forms, and conceptual play. This shift, once shocking, is now the grammar of contemporary image-making—from editorial design to 3D modeling. His relentless curiosity also spilled into sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, turning his studio into a laboratory for visual research. For context on other innovators who altered art’s trajectory, compare how Van Gogh’s expressive color paved the way for modern emotion-driven palettes through our collection of Vincent van Gogh wall art.

From Málaga to Paris: The Roots of a Revolution

Born in Málaga in 1881, Picasso received rigorous academic training from his father and Spanish academies. In Barcelona and later Paris, he met bohemians, poets, and patrons who sharpened his eye. The result wasn’t a rejection of tradition but a radical dialogue with it. He studied Old Masters obsessively, then deconstructed their solutions to build something new. If you’re tracing the origins of modernity more broadly, explore the classical-to-modern bridge in our Edouard Manet wall art collection—Manet’s bold realism primed audiences for jumps Picasso would later make.

How Picasso’s Style Evolved (and Why Each Phase Mattered)

The Blue Period (1901–1904)

In these years, Picasso painted elongated figures cloaked in indigo melancholy—musicians, beggars, mothers and children. The reduced palette became a psychological device, proving color alone can carry narrative weight. Even in sorrow, his surfaces experiment with composition and silhouette, preparing the ground for shape-driven revolutions to come.

The Rose Period (1904–1906)

Tones warm; subjects become acrobats, clowns, and performers. The circus world let Picasso explore balance, poise, and staged space—early cues for the compositional gymnastics of Cubism. Gentle pinks and ochres show how mood can pivot through hue shifts alone.

The African (Proto-Cubist) Period (1907–1909)

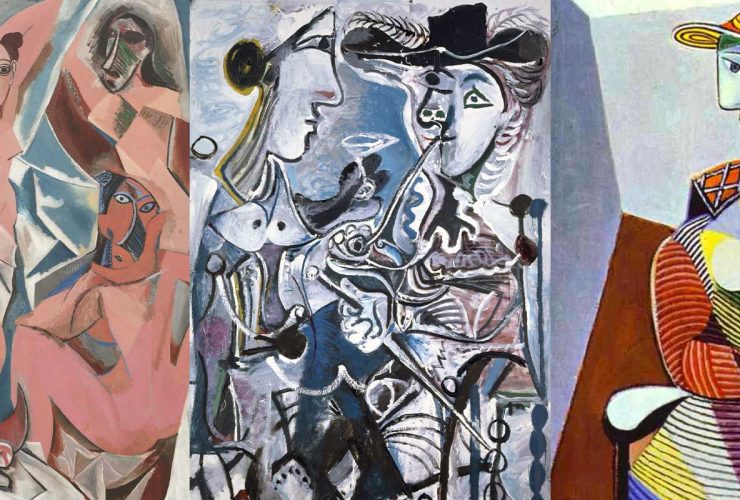

After encounters with African sculpture and Iberian forms, faces become mask-like; bodies harden into planes. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is the thunderclap—space fractures, gaze confronts, perspective collapses. The painting doesn’t just depict; it interrogates the act of looking.

For another lens on how masters orchestrate space, see how optical calm and order saturate Johannes Vermeer wall art—a useful foil to Picasso’s rupture.

Analytic Cubism (1909–1912)

Picasso (with Georges Braque) disassembles objects—violin, bottle, face—into semitransparent facets. Muted browns and grays keep attention on structure. Here painting behaves like philosophy in fragments; you don’t just view a subject, you reconstruct it.

Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919)

Color returns; collage enters. Wallpaper, newspaper, faux wood grain—materials become meaning. By pasting reality into the picture, Picasso dissolves boundaries between art and life. This phase foreshadows mixed media, graphic design, and even UI layering systems used today.

Classicism, Surreal Turns, and Ceramics (1920s–1940s)

Between wars, Picasso toggles between neoclassical solidity and biomorphic play. He also plunges into ceramics, proving innovation isn’t medium-specific. The throughline is restless reinvention—motifs mutate, but curiosity stays constant.

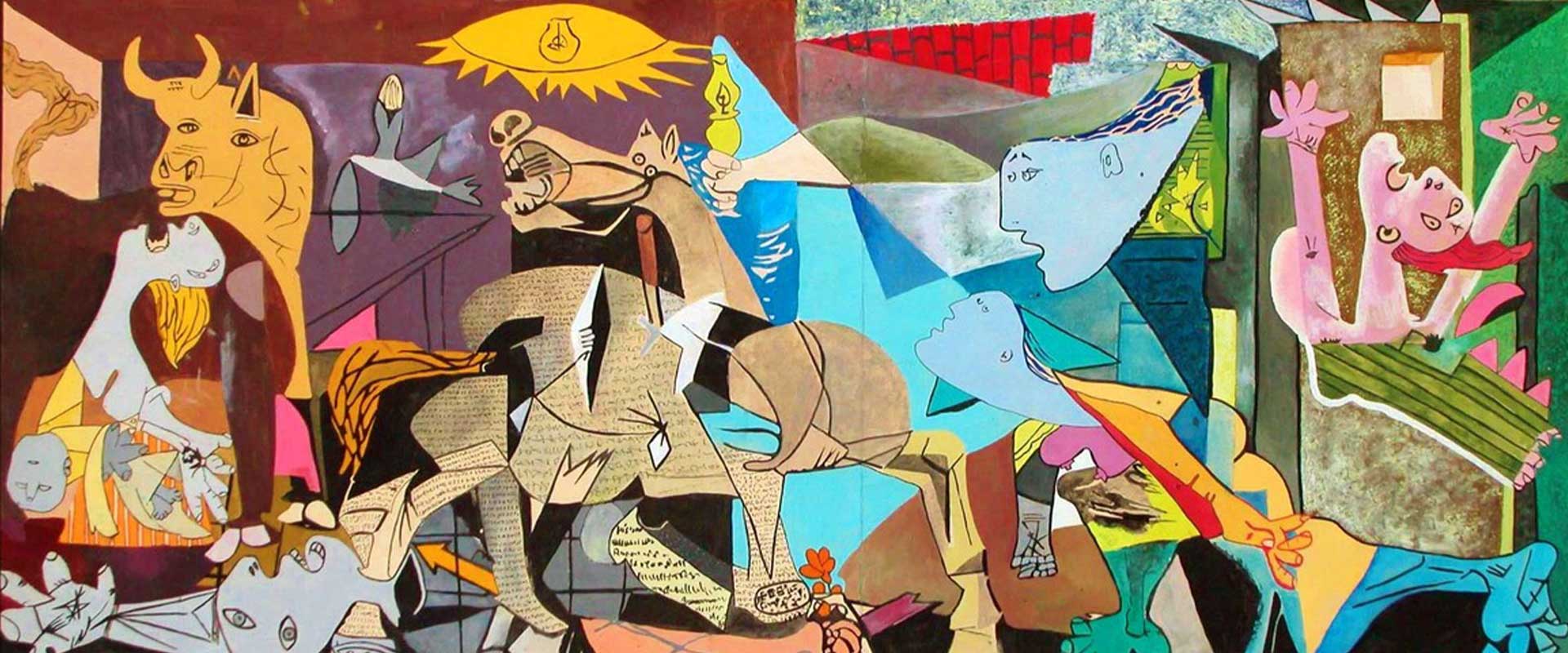

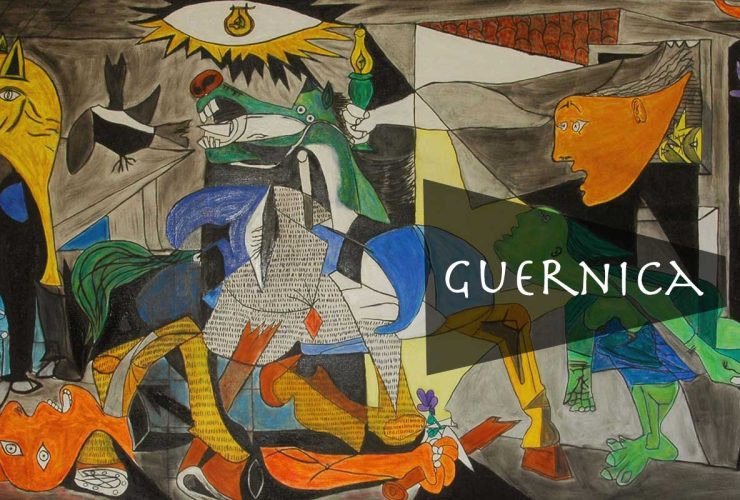

Guernica and Political Witness (1937)

Guernica transforms a news event into a visual dirge against brutality. The palette is ash; the forms are splintered; the narrative is universal. Painting becomes a public conscience—a role that echoes in activist imagery today. To see how other modern masters pursue emotion through color rather than fracture, browse our Pierre-Auguste Renoir wall art.

Late Work (1940s–1973)

Late Picasso is fierce, playful, and prolific. Bulls morph into glyphs; musketeers swagger; line becomes shorthand for lifelong memory. He quotes Old Masters, then bends them into his alphabet. The lesson is plain: style can be a verb, not a cage.

A Quick Timeline of Picasso’s Key Periods and Works

| Period | Years | Core Moves | Representative Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | 1901–1904 | Monochrome mood, elongated forms | The Old Guitarist, La Vie |

| Rose | 1904–1906 | Warmer palette, circus figures | Family of Saltimbanques, Harlequin |

| African/Proto‑Cubist | 1907–1909 | Mask-like faces, planar bodies | Les Demoiselles d’Avignon |

| Analytic Cubism | 1909–1912 | Faceting, limited color, multiple viewpoints | Portrait of Ambroise Vollard |

| Synthetic Cubism | 1912–1919 | Collage, brighter hues, built forms | Still Life with Chair Caning |

| Political/Hybrid | 1930s–1940s | Monumental allegory, symbolism | Guernica, The Weeping Woman |

| Late Style | 1945–1973 | Quotations, speed, graphic line | Musketeer series, late prints |

This table is a shorthand—each line condenses a storm of experiments happening in parallel across media. For a complementary journey through a Renaissance-to-Modern arc, compare the measured harmony of Leonardo da Vinci wall art with Picasso’s willful disruption.

The Five Big Ideas Picasso Gave to Painting

1) Painting as Thought

Instead of mirroring the world, Picasso treated painting as a tool for thinking. Analytic Cubism reads like a diagram of perception—how mind and eye reassemble reality. This liberated artists to prioritize concept over imitation.

2) Multiple Viewpoints at Once

By showing several angles simultaneously, Picasso replaced single-point perspective with time-packed space. Motion, memory, and viewpoint could coexist on one plane—an idea that undergirds everything from motion graphics to AR interfaces.

3) Materials as Meaning

With collage, Picasso turned everyday stuff into structure. Newspaper added context; rope framed a café table; faux textures teased illusion. He expanded painting’s vocabulary to include the world itself.

4) Tradition as Raw Material

Picasso quoted, wrestled, and re-authored the Old Masters. He didn’t bow to tradition; he conversed with it—a playbook artists still use to remix cultural memory. For another example of dialoguing with precedent, see Frida Kahlo wall art, where symbolism and identity fuse with art history.

5) Art as Civic Voice

From Guernica onward, Picasso demonstrated that a painting can be civic speech—not just private feeling. In a century of upheaval, he made the canvas a place for public ethics.

Techniques: How Picasso Engineered New Visual Language

Faceting and Planarity

Objects are sliced into facets that interlock like crystalline tiles. This lets surfaces carry simultaneous front, side, and memory views. The trick: keep tonal steps subtle so the eye glides between shards.

Palette Control as Narrative

Blue and Rose periods prove color can write mood. In Cubism, restricting hues to browns and grays spotlights geometry; in Synthetic Cubism, reintroducing color and collage re-energizes readability.

Collage: From Illusion to Allusion

Wallpaper swatches and newsprint announce the artifice of representation. You don’t just see a café table—you feel its context, its time stamp, its material culture.

Line as Memory Script

Late drawings compress decades into swift, declarative strokes. Economy of line becomes a signature of confidence and recall.

For a contrasting approach where optical serenity rules, examine the quiet staging in Johannes Vermeer wall art. The comparison clarifies how Picasso weaponizes disruption, while Vermeer refines order.

Picasso and Other Masters: A Productive Tension

Modernism grows through productive disagreements. Where Van Gogh invests color with emotion, Picasso detaches color to focus on structure—then later reloads it for collage. Where Manet flattens space to confront the viewer, Picasso shatters space to involve the viewer in reconstruction. Where Da Vinci idealizes anatomy, Picasso re-codes anatomy as geometry. This network of tensions is why his influence extends beyond painting into architecture, typography, and digital media. To see these dialogues in print-friendly form, browse Artists at Canvas Wall Prints.

Collecting Picasso (Reproductions, Styles, and Display Tips)

If you love Picasso’s language of forms, reproductions offer approachable entry points.

- Blue/Rose mood pieces: perfect for bedrooms and reading nooks; pair with muted textiles to let color temperature breathe.

- Analytic Cubism: powerful in studies and offices—its thinking-in-facets vibe suits focus zones.

- Synthetic Cubism & collages: great in dining rooms and social spaces; the material play sparks conversation.

- Political works: hallways and living rooms—spaces where images meet discussion.

For a softer counterpoint to Cubist edge, consider the lyrical textures in Pierre-Auguste Renoir wall art to balance a gallery wall.

How Picasso’s Ideas Live in Today’s Visual Culture

Picasso’s logics—faceting, overlapping planes, collage—are now industry defaults. UI designers layer cards and shadows; photographers double-expose; animators split forms across time. Even data visualization borrows Cubist multi-perspectival thinking, inviting viewers to reconstruct patterns across planes. The lesson for creators is clear: make process visible. The audience won’t mind the scaffolding; they’ll trust it.

Key Questions (and Clear Answers)

How did Picasso transform painting?

He replaced single-view realism with multi-view construction. Through Cubism, he treated perception as a puzzle to be assembled on the canvas. Collage turned materials into meaning; political works turned painting into civic language. In short, he moved art from description to investigation.

How can you spot Analytic vs. Synthetic Cubism?

Analytic: muted palette, dense faceting, objects dissected. Synthetic: brighter colors, larger shapes, forms built from collage and painted textures.

How did Picasso use tradition?

He sampled Old Masters, then recomposed them. The point wasn’t homage; it was argument—asking what those solutions mean now.

How does his legacy compare with other icons?

Where Van Gogh amplifies emotion through color, Picasso engineers perception through structure. Where Renoir seeks sensual surfaces, Picasso tests visual grammar. Where Vermeer clarifies stillness, Picasso accelerates seeing.

For a curated jump across these voices, explore Leonid Afremov wall art for color-driven atmosphere that echoes—but never imitates—modernist intensity.

Practical Style Guide: Using Picasso-Like Principles at Home

- Pick your mood with palette. Blue/Rose tones for serenity; Cubist neutrals for cerebral calm; collage brights for social zones.

- Stage geometry. Repeat triangles, diamonds, and stripes in rugs, cushions, or frames to echo planar rhythms.

- Layer materials. Combine linen, wood, and metal to create synthetic harmonies—a room-scale tribute to collage.

- Balance with stillness. Pair a Cubist print with a calm landscape (try a serene classic from Johannes Vermeer wall art) so the eye alternates between inquiry and rest.

Conclusion

Picasso changed painting by changing what seeing means. He replaced the window-on-the-world with a workbench for perception, where forms are tested, remixed, and made to speak. From color as mood to collage as context and Cubism as thought, he built the toolkit we still use to make images today. If his audacity inspires you, start a conversation on your own walls with curated pieces from Canvas Wall Prints—then let geometry, color, and courage set the tone.

FAQs

What made Picasso different from his contemporaries?

He treated painting as an idea engine, prioritizing structure, process, and concept over likeness. This approach redefined modern aesthetics.

Is Picasso hard to “get”?

Start with Blue and Rose works to feel his emotional clarity. Then move into Cubism, reading shapes as notes in a chord rather than puzzle pieces.

Did Picasso only paint?

No—he worked in sculpture, ceramics, prints, and stage design. Each medium fed the others, expanding his toolkit.

Why is Guernica so important?

It proves a painting can be moral speech. Its scale, palette, and fractured forms deliver a universal message against violence.

What’s the easiest way to decorate with Picasso-inspired art?

Pick a period that matches your space’s mood and echo its geometry with furnishings. For ready-to-hang options, browse our Pablo Picasso wall art collection.