A Town Destroyed, a World Shocked

On April 26, 1937, the peaceful Basque town of Guernica was reduced to rubble in one of the most devastating aerial bombardments of the Spanish Civil War. German and Italian planes, supporting General Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces, carried out a brutal attack that left hundreds of civilians dead and the town center in ruins. News of the massacre quickly spread across Europe, sparking outrage. For Pablo Picasso, then living in Paris, these reports were impossible to ignore. What followed was not just a painting but a seismic statement—Guernica, an 11-foot tall and 25-foot wide mural that gave voice to the victims of war and positioned Picasso as both an artist and activist.

The tragedy of Guernica was not the first time Picasso confronted political themes, but it was the catalyst that turned his artistic expression into a universal symbol of protest. To understand the full story of the painting, it is essential to look at its historical context, the commission behind it, the symbols embedded within it, and its lasting influence on both art and society.

Picasso and the Spanish Civil War

By the mid-1930s, Spain was torn apart by ideological conflict. The Spanish Civil War pitted Republicans—composed of leftists, liberals, and workers—against Franco’s Nationalist forces, who received support from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Picasso, though living abroad, was appointed honorary director of Madrid’s Prado Museum in 1936, a symbolic gesture that tied him more deeply to his homeland’s struggles.

Initially, Picasso had not taken on overtly political commissions. His earlier work leaned heavily on innovation and personal exploration, from his Blue and Rose Periods to the Cubist revolution. However, the bombardment of Guernica shifted his focus. The attack was unprecedented in scale—it was one of the first times an entire civilian population was targeted with systematic aerial bombardment. Picasso’s Guernica became an immediate reaction to this modern horror, making it one of the earliest large-scale artistic protests against mechanized warfare.

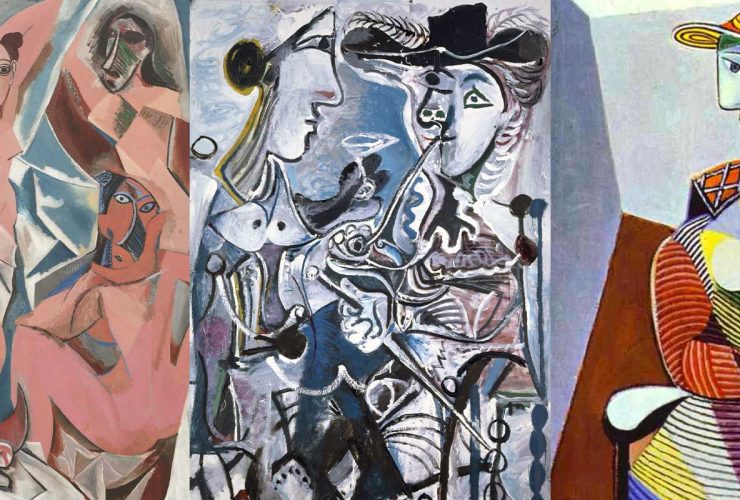

For readers exploring broader artistic responses to conflict, our guide to Famous Picasso Paintings That Redefined Modern Art places Guernica within a wider framework of his evolving creativity.

The Paris Exposition and the Commission

The Spanish Republican government had commissioned Picasso to create a mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition. Initially uninspired, he had been experimenting with other ideas. But once the news of the bombing reached Paris, his direction changed instantly. Within weeks, Picasso produced preparatory sketches, studies, and smaller works that built toward the monumental mural.

The pavilion itself was an act of resistance, showcasing the resilience of Spanish culture amid war. Alongside Guernica, the pavilion included works by Joan Miró and Alexander Calder. But Picasso’s mural dominated the exhibition, not just in size but in power. Its stark monochrome palette, fragmented figures, and raw emotional force set it apart from the optimism that many other pavilions sought to project.

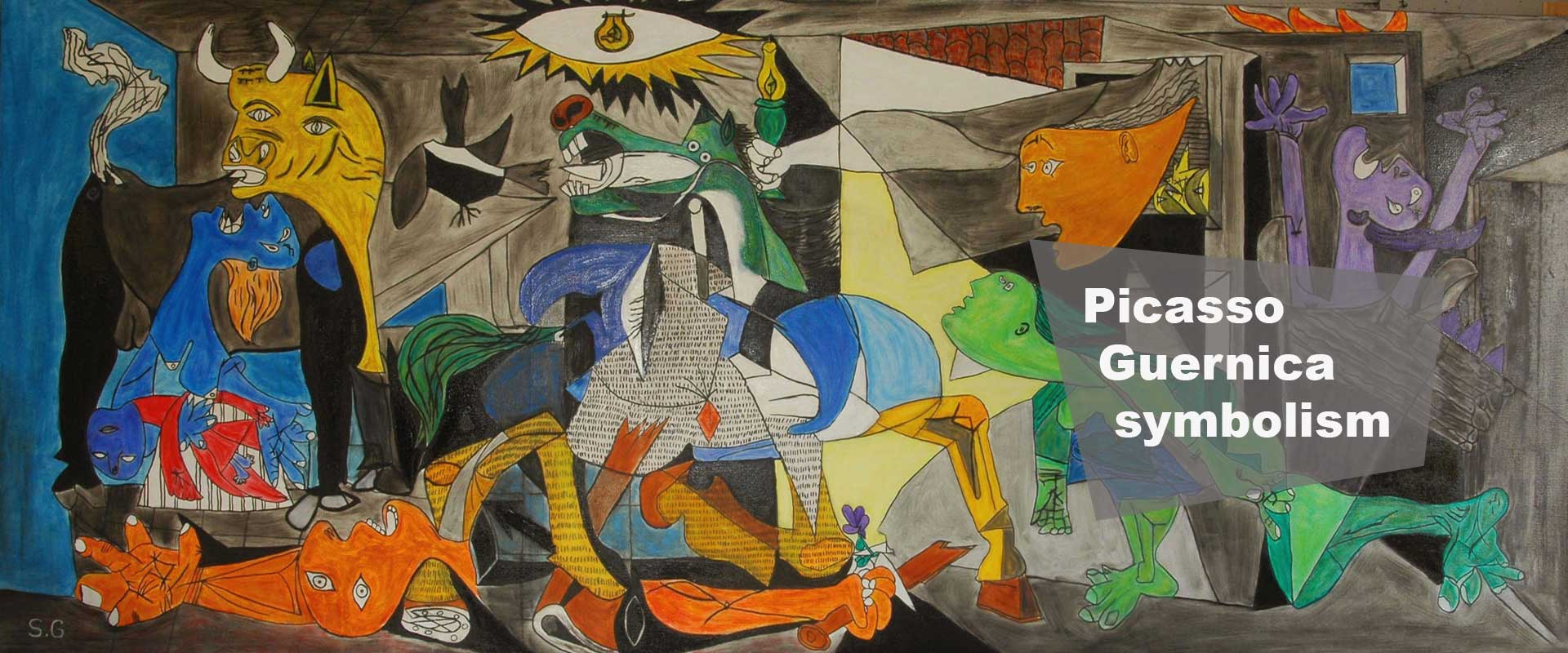

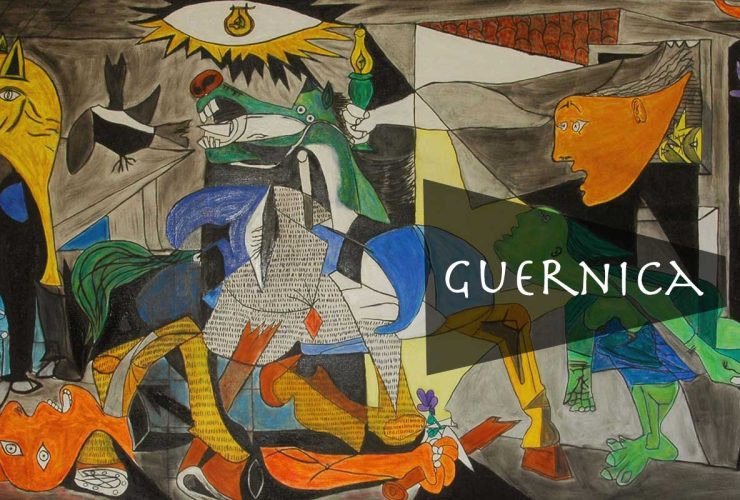

Breaking Down the Symbolism of Guernica

One of the reasons Guernica continues to capture global attention is the depth of its symbolism. Unlike narrative battle scenes of the past, Picasso chose allegory and abstraction to depict the horrors of modern war.

- The Bull: Positioned on the left, the bull is one of the most debated figures in the painting. Some interpret it as representing brutality, while others argue it symbolizes Spain itself, wounded but unyielding.

- The Horse: At the center, the wounded horse writhes in pain, often interpreted as the suffering of the Spanish people or humanity itself. Its open mouth and jagged body add to the sense of chaos.

- The Fallen Soldier: Beneath the horse lies a fragmented soldier, clutching a broken sword. From the broken weapon emerges a small flower, suggesting fragile hope amid destruction.

- The Mother and Child: To the left, a mother screams in grief as she cradles her lifeless child. This figure is among the most emotionally powerful, embodying the civilian toll of war.

- The Woman with the Lamp: Emerging from a window, a woman holds a lamp that casts light over the chaotic scene. This figure may symbolize truth or resilience, countering the artificial glare of the overhead bulb.

- The Light Bulb (Eye of God or Eye of Technology): Above, the glaring electric light bulb dominates the composition. Its harshness suggests the cold, mechanical nature of modern warfare.

Unlike propaganda posters, Picasso did not create clear heroes or villains. Instead, he offered a fragmented vision that forced viewers to confront the devastation and draw their own conclusions.

The Black-and-White Palette

Picasso’s choice of grayscale was deliberate. Some art historians argue that it reflects the black-and-white photographs of Guernica’s aftermath published in newspapers. The lack of color also strips the scene of any beauty or romanticism, presenting war in its starkest reality. The monochrome palette transforms the mural into something closer to a historical record or collective memory rather than just a painting.

Public Reception in 1937

When Guernica debuted in Paris, it stunned viewers. Many visitors expected a celebratory or patriotic mural. Instead, they encountered a harrowing, abstracted protest. While some critics dismissed its distortions as incomprehensible, others immediately recognized its importance. The mural’s touring exhibitions later that year across Europe and the United States drew attention to Spain’s plight and gave international visibility to the anti-fascist cause.

At the time, Picasso’s painting was not universally accepted in Spain. For supporters of Franco, it was viewed as subversive propaganda. But for exiles and Republicans, it became a rallying point, symbolizing the resilience of those who resisted authoritarianism.

Guernica’s Journey Through the World

After the 1937 exhibition, Guernica traveled extensively, appearing in London, New York, and other major cities. These tours raised awareness of the Spanish Civil War while solidifying the painting’s reputation as a universal anti-war icon.

During World War II, Picasso’s mural remained politically relevant. Famously, when a Nazi officer reportedly questioned Picasso about Guernica, asking, “Did you do this?” Picasso is said to have responded: “No, you did.” Whether apocryphal or not, the story underscores the painting’s enduring link to war crimes and civilian suffering.

In 1939, as Franco solidified power in Spain, Guernica was placed in the custody of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Picasso stipulated that it should not return to Spain until democracy was restored. True to his wish, the painting remained in New York for over four decades.

Return to Spain and Its Home in Madrid

After Franco’s death in 1975, Spain began its transition to democracy. In 1981, Guernica was finally returned to Spanish soil, arriving at the Prado Museum before being permanently relocated to the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid in 1992. Its installation there gave Spain a powerful cultural treasure—one that continues to draw millions of visitors annually.

Today, the Reina Sofía dedicates an entire gallery to Guernica and its preparatory sketches, allowing viewers to trace Picasso’s creative process. For travelers, visiting the museum offers a chance not only to witness the painting but also to experience it in the context of 20th-century Spanish history. For art lovers planning a trip, our in-depth guide on Tickets for Barcelona’s Best Museums Including the Picasso Museum is a useful complement.

Picasso’s Techniques and Innovations

Beyond its subject matter, Guernica represents a pinnacle of Picasso’s mastery of form. He drew on Cubism’s fragmented planes, Surrealism’s distortions, and classical references to create a multi-layered composition. The large scale of the painting demanded a level of physicality—Picasso used bold strokes, charcoal lines, and rapid improvisations.

His preparatory studies reveal how much experimentation went into the mural. Early sketches included more figures, but Picasso pared them down to focus on essential, symbolic elements. This process highlighted his ability to strip a subject to its raw core while retaining emotional intensity.

Guernica and Political Art

Guernica is often cited as the most powerful political artwork of the 20th century. Its influence extended beyond Spain, inspiring generations of artists and activists. During the Vietnam War, the painting was reproduced in protest posters. In 2003, a tapestry replica displayed at the United Nations headquarters was famously covered during U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s speech advocating for war in Iraq—proof that the painting remained uncomfortably relevant decades later.

Other modern artists, such as Jackson Pollock, influenced by Picasso’s raw energy, and more contemporary political muralists, have acknowledged Guernica as a touchstone. It transcended its historical moment, evolving into a universal condemnation of war.

Comparative Context: Guernica and Other Anti-War Art

Throughout history, artists have responded to war with works that seek to capture its tragedy. Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 similarly portrays the brutality of civilian executions during the Peninsular War. Otto Dix’s World War I etchings expose the grotesque reality of trench warfare. Yet, Picasso’s Guernica stands apart in its abstraction. By refusing to depict the bombing literally, he created a timeless representation of suffering that resonates beyond a specific event.

Interpretations Through Time

Over the decades, scholars have debated the meanings embedded in Guernica. Some see the bull as Franco himself, while others argue it is a symbol of endurance. The flower near the broken sword is often highlighted as the sole symbol of hope. The woman with the lamp may represent enlightenment piercing the darkness of war.

Picasso himself resisted assigning fixed meanings, often frustrating interviewers. He insisted that the painting was universal, meant to be interpreted broadly. This openness has allowed the work to remain relevant in changing contexts, from World War II to modern conflicts.

Guernica as a Cultural Touchstone

Today, Guernica appears in textbooks, exhibitions, and political debates. Its imagery has been reproduced on posters, banners, and murals across the world. Activists continue to use it as shorthand for civilian suffering. Its power lies in its ability to transcend cultural and temporal boundaries—any viewer, regardless of background, can feel its anguish.

At the Reina Sofía, the experience of standing before Guernica remains overwhelming. Its sheer size forces viewers into confrontation, while its fragmented style invites close reading. The painting reminds us not only of a particular atrocity but of war’s capacity to devastate ordinary lives anywhere.

Legacy of Guernica in Modern Spain

For Spain, Guernica is both a painful reminder and a cultural treasure. It connects to the unresolved memory of the Spanish Civil War, a subject that still sparks debate. It also represents Spain’s cultural resilience, a masterpiece created in exile that now stands at the heart of its democratic identity.

Cultural institutions in Spain frequently draw connections between Guernica and other masterpieces of resistance art. For example, exhibits at the Picasso Museum Barcelona often place the mural’s preparatory works alongside earlier experiments, offering visitors a holistic understanding of his evolution. To enrich a visit, travelers may explore our guide to Picasso Museum Barcelona: What to See and How to Plan Your Visit, which complements the story of Guernica by exploring his broader legacy.

Conclusion: Why Guernica Still Matters

More than eight decades after its creation, Guernica continues to resonate. It stands as a powerful reminder that art can be both deeply personal and universally political. Picasso transformed the suffering of a small Basque town into a monumental cry for humanity. The painting’s symbolism, its journey across continents, and its continued relevance in political discourse ensure that Guernica is not just a masterpiece of modern art but one of the most important cultural landmarks in human history.

Its relevance today lies in its refusal to lose urgency. In a world still plagued by conflict, Guernica insists on being seen, remembered, and felt. Standing before it in Madrid is not merely an aesthetic experience but a confrontation with history, morality, and human resilience.